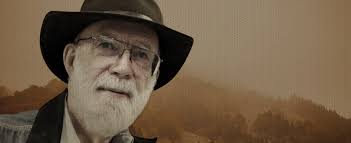

Michael Harner

Shamanic Healing: We Are Not Alone

What’s really important about shamanism, in my opinion, is that the shaman knows that we are not alone. By that I mean, when one human being compassionately works to relieve the suffering of another, the helping spirits are interested and become involved.

The word “shaman” in the original Tungus language refers to a person who makes journeys to nonordinary reality in an altered state of consciousness. Adopting the term in the West was useful because people didn’t know what it meant. Terms like “wizard,” “witch,” “sorcerer,” and “witch doctor” have their own connotations, ambiguities, and preconceptions associated with them. Although the term is from Siberia, the practice of shamanism existed on all inhabited continents.

After years of extensive research, Mircea Eliade, in his book, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, concluded that shamanism underlays all the other spiritual traditions on the planet, and that the most distinctive feature of shamanism—but by no means the only one—was the journey to other worlds in an altered state of consciousness.

Shamans are often called “see-ers” (seers), or “people who know” in their tribal languages, because they are involved in a system of knowledge based on firsthand experience. Shamanism is not a belief system. It’s based on personal experiments conducted to heal, to get information, or do other things. In fact, if shamans don’t get results, they will no longer be used by people in their tribe. People ask me, “How do you know if somebody’s a shaman?” I say, “It’s simple. Do they journey to other worlds? And do they perform miracles?”

The practice of shamanism is a method, not a religion. It coexists with established religions in many cultures. In Siberia, you’ll find shamanism coexisting with Buddhism and Lamaism, and in Japan with Buddhism. It’s true that shamans are often in animistic cultures. Animism means that people believe there are spirits. So in shamanic cultures, where shamans interact with spirits to get results such as healing, it’s no surprise that people believe there are spirits. But the shamans don’t believe in spirits. Shamans talk with them, interact with them. They no more “believe” there are spirits than they “believe” they have a house to live in, or have a family. This is a very important issue because shamanism is not a system of faith.

Shamanism is also not exclusionary. They don’t say, “We have the only healing system.” In a holistic approach to healing, the shaman uses the spiritual means at his or her disposal in cooperation with people in the community who have other techniques such as plant healing, massage, and bone setting. The shaman’s purpose is to help the patient get well, not to prove that his or her system is the only one that works.

In many cultures, shamans are often given gifts for their work, but they will return all the gifts if the patient dies, which I think is a commendable innovation that might help us with the costs of health services today.

Shamans talk with plants and animals, with all of nature. This is not just a metaphor. They do it in an altered state of consciousness. Our own students rapidly discover that by talking with plants, they can discover how to prepare those plants for remedies. Shamans have been doing this since ancient times. They typically know a great deal about plants, but it’s not essential. For example, Eskimo shamans don’t have access to a lot of plants, so they work with other things. But in the Amazon shamans know the various plants and the songs that go with the plants, which they commonly learn from the plants themselves.

One former student of mine in the United States developed a practice of discovering and using healing plants based on his learning directly from the plants. He found that the pharmacopoeia he developed was very close to the ancient, classic Chinese pharmacopoeia knowledge of how to prepare and use these plants for different ailments. Another former student in Germany worked with minerals and found how they could be used in healing. It turned out that her discoveries were very close to what has been known in India from ancient times.

Which brings us to a very important issue: everything that’s ever been known, everything that can be known, is available to the shaman in the Dreamtime. That’s why shamans can be prophets; that’s why they can also go back and look at the past. With discipline, training, and the help of the spirits, this total source of knowledge is accessible.

The founder of the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, MICHAEL J. HARNER (1929-2018) pioneered the introduction of shamanism and the shamanic drum journey to contemporary life and is recognized as the world leader in this movement.

In his half-century of anthropological fieldwork, cross-cultural studies, experimental research, and firsthand experience, Harner arrived at the core methods of shamans worldwide. The applicability of this core shamanism to contemporary Westerners has been substantiated by the experiences of his thousands of students. The experiential methods are simple, safe, and have been used successfully by them with positive life-changing results.

Honoring the oral tradition of indigenous shamans, for the last quarter of a century Harner conveyed his shamanic knowledge first-hand through teaching and experiential work rather than through writing.

Michael Harner is not just an anthropologist who has studied shamanism; “he is an authentic white shaman,” observes the distinguished transpersonal psychologist Stanislav Grof. Harner began learning about shamanism in 1956-57 while studying with the Shuar (Jívaro) tribe of the Ecuadorian Amazon and started practicing shamanism during his 1960-61 stay with the Conibo people of the Peruvian Amazon. He subsequently returned to the Shuar for additional practical training in shamanism. He became recognized as a shaman by the indigenous shamans with whom he worked, including ones belonging to the following peoples: the Conibo and Shuar (formerly Jívaro) in South America; the Coast Salish, Pomo, and Northern Paiute in western North America; the Inland Inuit and the Sami (formerly Lapps) in the Arctic; and the Tuvans of central Asia.

In Russia, assembled Siberian shamans of the Buriat people publicly declared Michael Harner a great shaman upon witnessing his shamanic healings in 1998 (the word, shaman, comes from Siberia). They also said he proved that one could do both science and shamanism.

Perhaps Harner’s greatest contribution has been his pivotal role in bridging the worlds of indigenous shamanism and the contemporary West through his fieldwork and research, experimentation, writings, and original development of the core methods of shamanism. By introducing these methods to the West, he started the movement that is returning shamanism and shamanic healing to the spiritual life of peoples throughout the planet.

Michael Harner received his anthropology Ph.D. in 1963 from the University of California, Berkeley, and has taught at various institutions, including UC Berkeley, Columbia University, Yale University, and the Graduate Faculty of the New School in New York, where he was chair of the anthropology department. He also served as co-chair of the anthropology section of the New York Academy of Sciences. He left academia in 1987 in order to devote himself fulltime to shamanism. In 2003 he received an honorary doctorate in recognition of his achievements in shamanic studies. In 2009, he was honored by California Pacific Medical Center’s Institute for Health & Healing with the “Pioneers in Integrative Medicine Award.” He also received special academic recognition through the presentation of sessions dedicated to him at the 2009 annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association in Philadelphia. Three organizations of the AAA joined together to recognize him for his “pioneering work” in shamanism “as an academic and advocate” and for his role during the last forty years in the “exponential growth in anthropological studies of the importance and significance” of shamanism.

His books include The Way of the Shaman (Harper & Row), Hallucinogens and Shamanism (Oxford University Press), The Jívaro (University of California Press), and a novel, Cannibal, which he co-authored. His latest book Cave and Cosmos: Shamanic Encounters with Another Reality was released April 9, 2013.